Decision-making & Behavioral Biases

Action bias

Actor–observer bias

Ambiguity effect

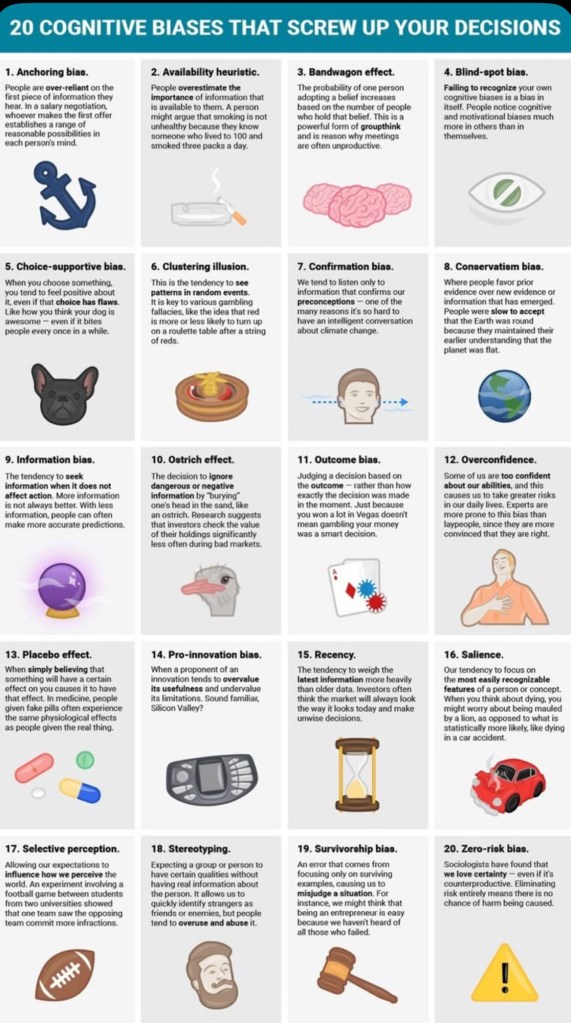

Anchoring bias

Anthropic bias

Attentional bias

Availability heuristic

Availability cascade

Backfire effect

Bandwagon effect

Base rate fallacy

Belief bias

Bias blind spot

Bystander effect

Choice-supportive bias

Clustering illusion

Commitment bias

Conservatism bias

Continuum fallacy

Contrast effect

Courtesy bias

Cynicism bias

Decoy effect

Default effect

Denomination effect

Dunning–Kruger effect

Duration neglect

Empathy gap

Endowment effect

Escalation of commitment

Evaluation apprehension

Exaggerated expectation

Experimenter’s bias

False consensus effect

False uniqueness bias

Focusing effect

Forer effect

Framing effect

Frequency illusion

Functional fixedness

Gambler’s fallacy

Goal gradient effect

Group attribution error

Groupthink

Halo effect

Hard-easy effect

Herding effect

Hindsight bias

Hot-hand fallacy

Hyperbolic discounting

Identifiable victim effect

IKEA effect

Illusion of control

Illusion of transparency

Impact bias

Implicit bias

Information bias

Insensitivity to sample size

Intergroup bias

Irrational escalation

Just-world hypothesis

Law of the instrument

Less-is-better effect

Loss aversion

Mere exposure effect

Moral luck

Naïve realism

Negativity bias

Neglect of probability

Normalcy bias

Not invented here bias

Observer-expectancy effect

Omission bias

Optimism bias

Outcome bias

Overconfidence effect

Pareidolia

Parkinson’s law of triviality

Peak–end rule

Peltzman effect

Planning fallacy

Post-purchase rationalization

Pro-innovation bias

Projection bias

Pseudocertainty effect

Reactive devaluation

Recency bias

Restraint bias

Risk compensation

Selective perception

Semmelweis reflex

Shared information bias

Social comparison bias

Social desirability bias

Spotlight effect

Status quo bias

Stereotyping

Sunk cost fallacy

Survivorship bias

System justification

Time-saving bias

Third-person effect

Trait ascription bias

Unit bias

Wishful thinking

Zero-risk bias

Memory Biases

Absent-mindedness

Childhood amnesia

Cryptomnesia

Egocentric bias

Fading affect bias

Google effect (digital amnesia)

Hindsight bias (memory version)

Leveling and sharpening

Misinformation effect

Misattribution of memory

Modality effect

Mood congruent memory

Persistence

Picture superiority effect

Rosy retrospection

Self-relevance effect

Source confusion

Spare-time effect

Telescoping effect

Testing effect

Tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon

Verbatim effect

Von Restorff effect

Zeigarnik effect

Social & Interpersonal Biases

Affiliation bias

Authority bias

Beneffectance

Cheerleader effect

Confirmation bias

Courtesy bias

Defensive attribution

Disposition effect

Effort justification

Egalitarianism bias

Empathy gap

False consensus effect

Fundamental attribution error

Gender bias

Group-serving bias

Halo effect

Horn effect

Illusory superiority

Ingroup bias

Intergroup sensitivity effect

Just-world hypothesis

Moral credential effect

Naïve cynicism

Naïve realism

Outgroup homogeneity bias

Overjustification effect

Self-serving bias

Shared information bias

Social proof

Sympathy bias

Probability, Logic & Math Errors

Anecdotal fallacy

Base-rate neglect

Conjunction fallacy

Hot-hand fallacy

Illusory correlation

Ludic fallacy

Masked man fallacy

Probability matching

Prosecutor’s fallacy

Regression to the mean

Simplicity bias

Zero-sum bias

Belief, Ideology & Perception Biases

Apophenia

Authority heuristic

Belief perseverance

Confirmation bias

Disconfirmation bias

Essentialism

Magical thinking

Narrative fallacy

Optimism bias

Pessimism bias

Placebo effect

Priming

Representativeness heuristic

Salience bias

Selective exposure

Self-fulfilling prophecy

Superstitious learning

Doomscrolling bias

Outrage bias

Virality bias

Algorithmic confirmation bias

FOMO bias

Echo chamber effect