There was a time when the desert glittered brighter than any crown.

From the banks of the Tigris rose a city so enlightened, it made the rest of the world look like it was still rubbing sticks together for fire.

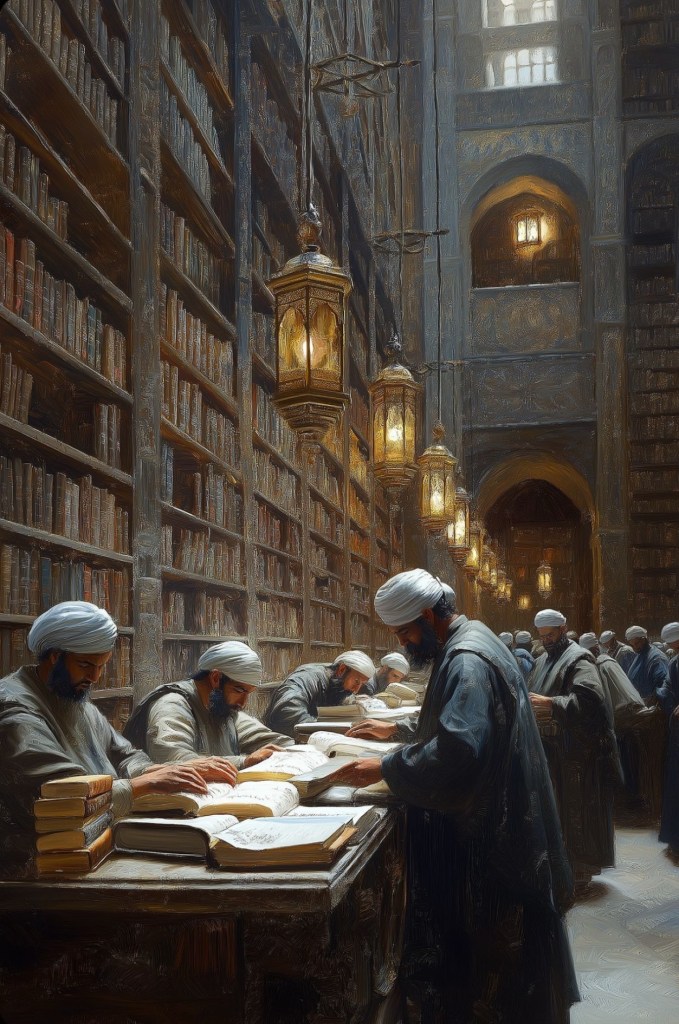

This was Baghdad, the jewel of the Abbasid Caliphate, and within it stood the Bayt al-Hikma — the House of Wisdom.

A temple not of stone, but of knowledge.

⸻

A Civilization Obsessed with Learning

By the 9th century, Baghdad was not just a city; it was a living organism pulsing with intellect.

Its streets were lined with bookshops, its mosques doubled as schools, and its people — merchants, scholars, doctors, astronomers — carried ink-stained fingers as badges of honor.

The city had hospitals with separate wards, libraries open to the public, and astronomical observatories that made Europe’s candlelit monasteries look like caves.

While Europe stumbled through the Dark Ages, believing illness was caused by demons and eclipses were omens of wrath, Baghdad’s physicians were documenting surgical procedures and mapping the human eye.

While medieval kings in the West bathed once a year (if they were feeling fancy), the Abbasids built public baths with hot water, marble walls, and perfumed oils.

In Baghdad, a poor student could attend public lectures by philosophers quoting Aristotle in Arabic. In London, around the same time, people were still burning women for “witchcraft.”

That’s not history. That’s tragedy wrapped in ignorance.

⸻

The Dreamers of the House of Wisdom

Inside the House of Wisdom, languages mixed like perfumes in the air.

Greek, Syriac, Persian, Sanskrit, and Arabic — all whispered together.

Scholars didn’t care where an idea came from. Only that it was true.

There was Al-Khwarizmi, the mathematician who created algebra — al-jabr, meaning “the reunion of broken parts.” He literally invented the concept of algorithms that now run your phone, your bank, your flight systems.

There was Hunayn ibn Ishaq, the Christian physician who translated Galen’s medical texts, improved them, and taught others how to heal with science, not superstition.

There was Al-Razi, who diagnosed smallpox centuries before Europe even had the vocabulary for “virus.”

There was Ibn Sina, whose Canon of Medicine would rule European universities for 600 years.

In their hands, mathematics became art, astronomy became poetry, and medicine became mercy.

⸻

When the World Looked East

To understand the brilliance of Baghdad, imagine a world where everyone looked east for answers.

When European scholars wanted to learn, they traveled through Moorish Spain just to find Arabic texts.

When kings in France or Italy wanted physicians, they hired Muslims trained in Baghdad’s methods.

A traveler in the 10th century once wrote:

“If knowledge were a tree, its roots would be in Baghdad, and its fruits would fall upon every nation.”

The Islamic Golden Age wasn’t just about science. It was about attitude.

Where Europe saw sin, Baghdad saw curiosity.

Where others prayed for miracles, Baghdad built them.

⸻

Facts That Defy Imagination

1. Astronomers in Baghdad measured the Earth’s circumference with an error margin of less than 1%.

2. Engineers built automated fountains, hydraulic clocks, and mechanical devices centuries before da Vinci was even a thought.

3. Libraries held over a million manuscripts, catalogued and cross-referenced by topic, long before the printing press existed.

4. Education wasn’t elitist — even slaves could study if they showed intellect.

5. Women like Lubna of Cordoba and Fatima al-Fihri (who founded the world’s first university) were part of this tradition of scholarship.

Knowledge wasn’t male or female, Muslim or Christian — it was divine.

⸻

The End of Light

Then came the year 1258 — the year the stars went out.

The Mongols, under Hulagu Khan, stormed through Mesopotamia like a plague of iron and flame. Baghdad, that miracle of civilization, became their next conquest.

When they breached its walls, the city didn’t fight — it pleaded. Scholars, imams, doctors, and poets begged for mercy. Hulagu offered none.

For seven days, Baghdad drowned in blood. Its citizens — men, women, children, philosophers — were butchered without distinction.

And then, they turned to the libraries.

The House of Wisdom — that palace of reason — was emptied into the Tigris River.

Witnesses said the water ran black with ink, then red with blood.

Books that once held the sum of human discovery were used as stepping stones across the river by soldiers who couldn’t read their own names.

Astronomy charts turned to pulp. Medical scrolls melted into mud. Equations, poems, and prayers all became the same gray sludge at the bottom of the riverbed.

It was as if the Earth itself wept for what was lost.

⸻

The Bitter Irony

History, cruel as ever, played a trick:

Within a few decades, the very people who destroyed that civilization — the Mongols — converted to Islam.

By 1295, under Ghazan Khan, they embraced the very faith and culture they had nearly erased.

They found peace in the knowledge their ancestors had burned.

You could call that irony. Or maybe redemption.

⸻

Epilogue — The River Still Remembers

Centuries later, when historians speak of the Renaissance, they rarely admit it was Baghdad’s ghost that breathed life into Europe.

Those translated Greek texts, that algebra, those astronomical tables — they all traveled west, carrying the fingerprints of Arab and Persian scholars.

The House of Wisdom may have drowned, but its reflections still shimmer in every scientific journal, every algorithm, every medical book.

A poet once said, “When you burn a library, you burn your own memory.”

In 1258, humanity didn’t just lose Baghdad. It lost its mind.

But every act of learning, every moment of curiosity today — every time someone reaches for truth instead of comfort — is a whisper from that river, reminding us:

“The ink of the scholar is more sacred than the blood of the martyr.”

And that was Baghdad — before darkness fell.

Leave a comment